Statement of Faith

The following is a statement of faith I wrote a few years ago. It’s fairly detailed and provides Scripture references for nearly every statement. While it’s personal in that it is what I believe, I think this is an accurate and useful summary of various doctrines taught in the Bible.

(PDF version: Statement of Faith – Brian Watson)

Revelation

God is spirit (John 4:24). He is immaterial and invisible (1 Tim. 1:17; 6:16). He cannot be detected through empirical observation or scientific experimentation. If he is to be known, he must reveal himself. Indeed, God has revealed himself in his world, his works, and his Word: both the written Word and the incarnate Word, Jesus Christ.

God’s revelation of himself in nature is called general revelation. God has revealed himself in all that he has created. The heavens declare his glory (Ps. 19:1). God’s eternal power and divine nature can be known clearly from creation, though sinful humans have suppressed this knowledge (Rom. 1:18-20). God has revealed himself in his providential care for his creation (Acts 14:15-17). God can also be known by the conscience that each human possesses (Rom. 2:14-15). God has put eternity into man’s heart, so that man knows there is more to reality than this mortal life (Eccl. 3:11).

Yet general revelation is not sufficient. It does not tell humanity exactly who God is. It cannot save anyone; it can only condemn. It leaves humanity without an excuse (Rom. 1:20). To know God truly, humanity would need to hear his voice.

Within the scope of biblical history, God spoke to several individuals. He spoke to Adam and Eve (Gen. 2:16–17; 3:9–19), Noah (Gen. 6:13–21), and Abram (Gen. 12:1–3), among many others, from Solomon (1 Kgs. 3) to Elijah (1 Kgs. 19) to some of the disciples (Matt. 3:17; 17:5; John 12:28).

God also revealed himself to individuals in dreams, as we see with Abimelech (Gen. 20:3–7), Laban (Gen. 31:24), and Solomon (1 Kgs. 3:5–14), and visions, as with Peter (Acts 10:9–16). Additionally, God appeared to some in physical manifestations, known as theophanies. Most famously, he appeared to Moses (Exod. 33:17–34:9), who was able to see God’s “back.” He also appeared to prophets such as Isaiah (Isa. 6).

Though in the Old Testament God revealed himself in these ways, and spoke to his people through the prophets, in the fullness of time he sent his Son, his true Word (John 1:1–8; Gal. 4:4; Heb. 1:1–2). Whoever saw Jesus saw the Father (John 14:9), for Jesus is the true image of God (2 Cor. 4:4; Col. 1:15).

Of course, these truths are revealed in God’s written Word, the Bible. All of Scripture is inspired, breathed out by God (2 Tim. 3:16). God’s Word is sufficient to make people wise for salvation (2 Tim. 3:15), and it gives eternal life (Ps. 119:93; John 6:68), in the sense that if a person believes God’s Word, he or she will be saved from sin and hell, be adopted by God the Father, be indwelled by the Holy Spirit, and live with the triune God forever. God’s Word is also useful for teaching, correcting, training, and equipping the Christian for a life of holiness and good works.

The Bible is the product of both God and man. Those who wrote Scripture spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit (2 Pet. 1:19–21). Therefore, the Bible can say that the Holy Spirit spoke Scripture by the mouth of a human author (Acts 1:16; 4:25) and that the words of Scripture are the words of Christ (Heb. 10:5). Paul calls both Old Testament and New Testament writings “Scripture” (1 Tim. 5:18; cf. Deut. 25:4; Matt. 10:10; Luke 10:7), and Peter refers to Paul’s writings as Scripture (2 Pet. 3:15–16; see also 1 Thess. 2:13). Therefore, we conclude that the entire canon of Scripture is God-breathed, written by the hands of humans, but directed by God so that each word written was exactly what God intended. The various modes of Scripture writing range from dictation from God (Rev. 2:1, 8, 12, 18; 3:1, 7, 14) to a human author conducting historical research (Luke 1:1–4).

God’s Word is true (2 Sam. 7:28; Ps. 119:43, 160; Prov. 30:5; John 17:17). It is therefore perfect (Ps. 19:7) and pure (Ps. 12:6; 19:8). God does not lie (Num. 23:19; Tit. 1:2; Heb. 6:18), therefore, we can trust that his word is reliable.

God’s Word is eternal. It will last forever (Ps. 119: 89; Isa. 40:6–8; Matt. 24:35). It is not subject to change, either through subtraction or addition (Deut. 4:2; 12:32; Prov. 30:6; Rev. 22:18).

God’s Word is living and active (Heb. 4:12). It accomplishes God’s purposes (Isa. 55:10-11).

God also reveals himself through the process of illumination. Through the work of the Holy Spirit, people are born again (John 3:1–8), able to profess that Jesus is Lord (1 Cor. 12:3), and are taught spiritual truths that non-Christians are unable to understand (1 Cor. 2:6–16). When God’s Word is read or preached through the power of the Holy Spirit, then full conviction of sin is the result, enabling people to turn from idols to the living God (1 Thess. 1:4–5, 9). God is able to open up spiritual eyes (Ps. 118:18; 2 Cor. 3:12–16; Eph. 1:18), which allows people to see the truth, shining light into our hearts so that we would have “knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” (2 Cor. 4:6).

God

There is only one God: Yahweh, the God of the Bible. There is no other (Isa. 45:5–6). He is the true and living God (1 Thess. 1:9–10). He is spiritual/immaterial (John 4:24), personal (Exod. 3:14), and triune (Matt. 28:19).

God has eternally existed as one Being in three Persons. The fact that God is triune can be demonstrated in various passages in the Bible, such as Matthew 28:19 and 2 Corinthians 13:14. Moreover, at Jesus’ baptism, all three Persons were present: the Father (whose voice was heard from heaven), the Son (being baptized), and the Spirit (who came, like a dove, upon Jesus). This event is portrayed quite clearly in the three synoptic Gospels (Matt. 3:13–14; Mark 1:9–11; Luke 3:21–22). Further, we know that God is triune because of the following propositions: (1) God is one (Deut. 6:4; James 2:19); (2) the Father is God (Isa. 63:16; 64:8; John 6:27; 17:1–3; 1 Cor. 8:6; 2 Cor. 1:3; Eph. 1:3; 1 Pet. 1:2–3); (3) the Son is God (John 1:1–4; 20:28–29; Rom. 9:5; Tit. 2:13; 2 Pet. 1:1); (4) the Spirit is God (Acts 5:3–4; 2 Cor. 3:16–18); (5) the Father is not the Son; (6) the Father is not the Spirit; and (7) the Son is not the Spirit (these last three propositions are supported by the description of Jesus’ baptism, the entire Gospel of John, and various Trinitarian passages such as 2 Cor. 13:14 and Eph. 1:3–14).

The fact that God is triune means that God is personal and he is an inherently relational being. Therefore, the Bible can say that God is love (1 John 4:8, 16), because he has always possessed intra-Trinitarian love. Each Person of the Trinity is involved in salvation, for the Father elected and adopted his children and sent his Son; Jesus became man to die on the cross for our sins; and the Holy Spirit indwells Christians, enabling us to have a relationship with God and serving as a seal and guarantee of our salvation (Gal. 4:1–7; Eph. 1:3–14).

Additionally, all three Persons of the Trinity are eternal (Ps. 90:2; Heb. 9:14; Rev. 1:8) and they all played some role in creation (Gen. 1:1–2, 26-27; Job. 33:4; Ps. 33:6; John 1:1–3; Col. 1:15–16; Heb. 1:1–2). Therefore, the three Persons are equal in essence.

Jesus is not less divine than the Father. If Jesus were anything but God, redemption would be impossible. Only an eternal God could cover our sins eternally. If the Holy Spirit were not God, it would be impossible to be recreated spiritually and to be drawn into union with Christ. If God were Unitarian, and not Trinitarian, he would not be inherently relational, nor could he both be the one who punishes sin and the bearer of sin. Therefore, the errors of Arius and Sabellius (and their followers, such as Jehovah’s Witnesses) should be rejected.

The triune God is eternal (Ps. 90:2; Isa. 9:6), omnipotent (Ps. 115:3; Dan. 2:21; Rev. 4:8), omnipresent (Ps. 139:7–19; Jer. 23:23–24), and omniscient (Ps. 139:1-6; Prov. 15:3; 1 John 3:20). God knows the future, declaring the end from the beginning (Isa. 46:9–11). He works all things according to his will and he will fulfill his purposes (Eph. 1:11; Isa. 46:11). God created everything, seen and unseen, ex nihilo (Gen. 1; Acts 17:24; Heb. 11:3; Rev. 4:11). All things exist from God, through God, and to God (Rom. 11:36). God is King of kings and Lord of lords (1 Tim. 6:15; Rev. 17:14; 19:16). He is also wise and true. Jesus is said to be the truth (John 14:6) as well as our wisdom (1 Cor. 1:24, 30).

God is good and his steadfast love endures forever (1 Chron. 16:34; 2 Chron. 5:13; Ps. 106:1; Jer. 33:11; Mark 10:18). God is perfect (Matt. 5:48). He is immutable; his character and purposes do not change (Mal. 3:6). He gives every good gift (James 1:17) and he cannot lie (Num. 23:19; Tit. 1:2; Heb. 6:18). There is no darkness in God at all (1 John 1:5).

Another way to refer to God’s perfection and character is to speak of his holiness. Throughout the Bible, God is referred to as holy (Lev. 11:44; Ps. 99; Isa. 6:3; Rev. 15:4). He is a jealous God who demands exclusive worship and fidelity (Exod. 20:3-6; 34:14). His eyes are so pure he cannot look upon evil (Hab. 1:13). He is righteous (Ps. 145:17; Isa. 5:16) and a righteous Judge (Ps. 7:11). Therefore, God must punish sin (Exod. 34:7). Yet God is also gracious and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in love (Exod. 34:6).

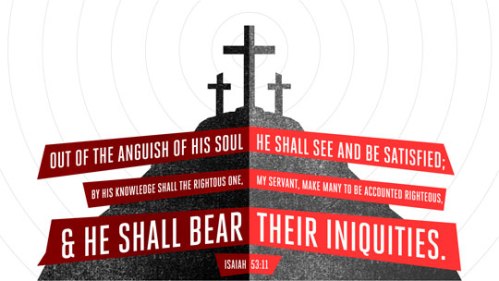

At the cross of Christ, God’s holiness and grace meet. By providing the perfect sacrifice for sin, God was able both to punish sin and to forgive his people their iniquities. The cross allows God to be just and the justifier of those who have faith in Christ (Rom. 3:21–26).

Creation and Providence

Creation

The witness of the Bible is clear: “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” (Gen. 1:1). Many passages indicate that God the Almighty is the Creator (Gen. 1–2; Neh. 9:6; Job 38–41; Isa. 42:5–6; 45:12; Acts 14:15; 17:24; Rev. 4:11; 10:6; 14:7). The three Persons of the Trinity were active in creation, for the Father created the world through the Son (Heb. 1:2; see also John 1:1–3). The Holy Spirit hovered over the waters at creation (Gen. 1:2) and Psalm 33:6 indicates that God created by his word and by his “breath” (rûaḥ, the same word translated as “Spirit”).

The eternal, triune God created the universe ex nihilo, out of nothing, speaking creation into existence through his Word. Hebrews 11:3 states, “By faith we understand that the universe was created by the word of God, so that what is seen was not made out of things that are visible.” This statement indicates that the visible universe was created by things that are not visible, which suggests that God created the universe out of nothing. In speaking of God’s creation of a people out of Abraham, Paul writes that God “gives life to the dead and calls into existence the things that do not exist” (Rom. 4:17). This statement also suggests that God brings things into being which did not exist. Colossians 1:16 says of Jesus, “For by him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him.” If “all things” is indeed absolute, this must include all energy and matter, as well as spiritual beings, animals, and human beings. Since the Bible speaks of God creating all things, and the Bible speaks of God existing eternally prior to creation (Ps. 90:2), it is a good and necessary inference to state that God created everything out of nothing.

The fact that God created everything else is vital, because it indicates that there is a clear distinction between Creator and creation. One is divine, the other is not. Therefore, the Christian doctrine of creation is far removed from pantheism. The earth is not divine. We are not divine. The Lord alone is God, and he freely chose to create the universe for his purposes.

All things were created for God, through God, and to God (Rom. 11:36). This means that creation exists for his glory. Indeed, the heavens declare God’s glory (Ps. 19:1), and God created his people for his glory (Isa. 43:6-7).

A number of implications flow from this doctrine. One, the fact that God created everything means he owns everything (Ps. 24:1–2; 89:11; 95:3-5). Two, the fact that God created everything shows that he is Lord (Jer. 33:2; Amos 9:6). Three, creation reveals God’s design and wisdom (as seen in the first two chapters in Genesis, as well as Prov. 3:19; 8:22–36; Jer. 10:12; 51:15). The world and all life forms did not come about by blind, mechanical forces, as those who advance some form of a macroevolutionary theory would have us believe. Four, the fact that God created everything shows that any miracle is possible. Five, the fact that God created everything means he can give life to those who are dead in their sins. Six, the fact that God created the universe means he can recreate it.

The last two implications require further explanation. The Bible likes God’s initial of act of creation to his recreation of individuals when they are born again. Second Corinthians 4:6 states, “For God, who said, ‘Let light shine out of darkness,’ has shone in our hearts to give the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ.” The God who is powerful enough to create the universe is certainly powerful enough to make us into new creations in Christ (2 Cor. 5:17).

The presence of sin in the world has led to a world that is under a curse. Romans 8:20–22 states that the creation has been subjected to futility, is in bondage to corruption, and is groaning—all because of the presence of sin. One day, when Jesus returns, there will be a new creation, which is promised in both the Old and New Testaments (Isa. 65:17–18; 66:22; 1 Pet. 3:10–13; Rev. 21:1).

Providence

The God of the Bible is the not the god of Deism. He is intimately involved with his creation. He provides for his creation, sustaining its existence at every moment, for, as Hebrews 1:3 states, Jesus upholds the universe by “the word of his power.” In Christ, all things hold together (Col. 1:17). God makes the sun to shine and the rain to fall on both the just and the unjust (Matt. 5:45). Rain, crops, and seasons all bear witness to God’s care for his creation (Ps. 104; Acts 14:17). He “knits” people in their mothers’ wombs (Ps. 139:13). He determines where and when they live (Acts 17:26). He clothes and feeds people (Matt. 6:25–34). He even numbers the hairs on their heads (Matt. 10:30).

Providence is typically thought of in three terms: preservation, concurrence, and governance. As stated above, God faithfully preserves his creation (Gen. 8:22). He also faithfully preserves his people (Pss. 31:23; 37:28; 66:9; 121:5–8; 138:7; 143:11; Matt. 16:18).

Of course, God’s providing for people also entails human effort. The way that God’s sovereign providence and human effort work together is called concurrence. God provides the ability work and earn wealth (Deut. 8:17–18), yet human diligence is lauded (Prov. 10:4; 12:24, 27; 13:4; 21:5), and human work is expected (1 Thess. 4:11; 2 Thess. 3:10). In many ways, God’s sovereign control over his creation works together with human effort. While humans can intend evil, God uses their efforts to cause a good result, as seen in the story of Joseph and, more importantly, in the crucifixion of Jesus (Gen. 50:20; Acts 2:23; 4:10, 27-28). Salvation (grace through faith leading to sanctification and glorification) is a gift from God, yet he expects us to work towards obedience and holiness (Phil. 2:12–13).

God clearly governs all his creation. He works all things according to the counsel of his will (Eph. 1:11). Whether light or darkness, well-being or calamity, God makes and directs all things, always carrying out his purposes (Prov. 16:4; Isa. 45:7; 46:8–12). He controls the hearts and fates of kings (Prov. 21:1; Dan. 2:21). Even the smallest occurrences are governed by God (Prov. 16:33).

Perhaps God’s greatest providence is salvation through his Son. Abraham knew that God would provide a substitutionary sacrifice, a lamb, for his son, Isaac (Gen. 22:8). Indeed, that sacrificial lamb is Jesus, provided to take away the sin of the world (John 1:29).

Humanity

God made humans in his image, to reflect his glory; he made humans male and female; and he made humans material and immaterial, consisting of both body and soul/spirit/mind.

On the sixth day, God created humans. They were the crowning glory of his creative works. God made man a little lower than the heavenly beings and crowned him with glory and honor (Ps. 8:5). Unlike anything else in creation, human beings were created in God’s image (Gen. 1:27) and were given the responsibilities of ruling over the earth, subduing it, being fruitful and multiplying, and working and guarding/keeping the garden of Eden (Gen. 1:26, 28; 2:15). Just as the priests and Levites guarded and kept the tabernacle (the same Hebrew verbs used of Adam in Gen. 2:15 are used in Num. 3, among other places, of the Levites), Adam and Eve were supposed to minister in the garden of Eden as God’s royal priests. Therefore, humans were created to work.

Being made in the image of God means, chiefly, imaging God in his world. In other words, human beings are made to represent God and to glorify him. (Isa. 43:6–7 says explicitly that God created his people for his glory.) Humans are able to image God because they reflect him in certain ways. God is personal (he is an agent who has a will), relational, rational, and he creative, among other things. Likewise, humans are persons, relational, rational, and creative. Yet humans are not divine. They are completely dependent upon God. They are finite and God is infinite.

Though humans have fallen into sin, they still bear God’s image (Gen. 9:6; James 3:9). However, this image is distorted by sin and therefore needs renewing. Humanity needs to be transformed into the true image of God, Jesus (Rom. 8:29; 2 Cor. 3:8; 4:4; Col. 1:15; 3:10).

God made human beings male and female (Gen. 1:27). Since both male and female are made in God’s image, they have equal value and dignity. Yet they have different roles in marriage (1 Cor. 11:2–16; Eph. 5:22–32; Col. 3:18–19; 1 Pet. 3:1–7) and in the church (1 Tim. 2:8-3:1–7; Tit. 1:5–9; 2:1–6). The fact that God made humans male and female means that God has defined human sexuality and that the definition of marriage is one man and one woman (Gen. 2:24).

God also made human beings both material and immaterial (Gen. 2:7 says that Adam was made from dust and the breath of God). In other words, humans are both body and soul/spirit/mind/heart (soul and spirit are used interchangeably at times, and Mark 12:30 states that God must be loved with heart, soul, mind, and strength). The body is not an inherently inferior or sinful substance, a prison from the which the spirit must escape. It was originally created very good (Gen. 1:31). Nor is the body all that humans are, in contradistinction from the worldview known as materialism. The material and immaterial aspects of human beings interact with each other in complex ways, so that to be fully human is to be both body and soul/spirit/mind/heart. Though in the intermediate state, the spirit/soul is separated from the body (2 Cor. 5:1–10), at the resurrection, the material and immaterial will be reunited for eternity.

Sin

In the beginning, there was no sin in God’s good creation. The only hint of the possibility of sin was sounded by God’s command to Adam: God told him not to eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, an action that would lead to death (Gen. 2:17). Yet sin entered the world through the actions of Adam and Eve (Gen. 3:6-7). Romans 5:12 says that sin came into the world through one man, Adam, who was the representative of all human beings. Of course, Eve was complicit in this transgression, too (1 Tim. 2:13–14). Because of this sin, all creation is under a curse (the natural implication of Rev. 22:3, which says that, in the new creation, there will no longer be anything accursed). God told Eve that women would have pain in childbearing, and she would desire to conquer her husband (Gen. 3:16; cf. Gen. 4:7). God told Adam that the ground would be cursed and that working for a living would be painful and difficult (Gen. 3:17–19). Death awaited the first two humans, but not before they left God’s direct presence in the garden of Eden (Gen. 3:23–24). Since then, all human beings have been born outside the direct presence of God, born in sin (Ps. 51:5), with Adam’s guilt imputed to them (Rom. 5:12–18). Whether we like it or not, all human beings are represented by the first Adam or the last Adam, Jesus. All are “by nature children of wrath” (Eph. 2:3). All have sinned and fallen short of the glory of God (Rom. 3:23). There is no one who is good (Rom. 3:9–18).

Sin creates a separation between God and man (Isa. 59:2), one that cannot be bridged by man’s best efforts. All are unclean, and even our righteous deeds are like a polluted garment (Isa. 64:6). Prior to redemption, humans are slaves to sin (John 8:34; Rom. 6:16, 19, 20). The just punishment for the sinner is death (Ezek. 18:4; Rom. 6:23; James 1:15).

Sin creates alienation between human beings, which is evidenced in all human history since the original sin of Adam. This separation between human beings is illustrated by Cain’s murder of Abel (Gen. 4:8).

Sin also creates an alienation within a person, causing the person to be dominated by sinful desires (2 Pet. 2:19). Sin causes one to have futile thought and darkened hearts (Rom. 1:21), which are deceitful and sick (Jer. 17:9). The “earthly” and sinful passions that wage war in us include sexual immorality, evil desires, and covetousness, which is idolatry (Col. 3:5).

Sin can be described in numerous ways, such as disobedience (Rom. 5:19), a lack of faith (Rom. 14:23), lawlessness (Rom. 6:19; 2 Cor. 6:14; 1 John 3:4), and transgressing the covenant (Hos. 6:7). The heart of sin is idolatry. Idolatry in the Bible is often depicted as spiritual adultery. Worship of false gods leads to disobedience to the true God’s commands. (James 4:1-4 connects idolatry with sinful passions, which leads to covetousness, fighting, and even murder.) One cannot serve both God and money (Matt. 6:24), and the love of money, like the love of all idols, is a root of all kinds of evils (1 Tim. 6:10).

The only cure for sin is Jesus Christ, who, though he knew no sin, became sin on the cross so that we might become righteous (2 Cor. 5:21). Jesus nailed our debt to the cross so that we might be forgiven or our trespasses (Col. 2:13–14).

Jesus

I believe that Jesus is the Christ (Matt. 16:16; Acts 2:36), the Son of God (Matt. 26:63–64; Luke 1:35; John 11:4; 1 John 4:15). Jesus is truly God, the second Person of the Trinity (John 1:1; 20:28; Rom. 9:5; Tit. 2:13; 2 Pet. 1:1). Jesus is one through whom the Father created the universe (John 1:3; Col. 1:16; Heb. 1:2). Jesus is both Lord and Savior (Luke 2:11; John 20:28; Acts 2:36). He is our great High Priest (Heb. 4:14–15; 8:1), the one mediator between God and man (1 Tim. 2:5).

In “the fullness of time . . . , God sent forth his Son, born of woman, born under the law, to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoptions as sons” (Gal. 4:4–5.) Jesus was born of the virgin Mary (Matt. 1:18, 23, 25; Luke 1:17, 34–35). By becoming flesh (John 1:14), Jesus did not lose his divine nature; rather, he added a human one, so that he is one Person who is fully God and fully man. He lived a sinless life (Heb. 4:15; 1 Pet. 2:22; 1 John 3:5), fulfilling the Mosaic law (Matt. 5:17; Rom. 10:4).

Jesus also died for our sins on the cross, bearing the wrath of God that we deserve (Matt. 20:28; John 1:29; 1 Cor. 15:3; Gal. 1:4; 1 Pet. 2:24). He was buried in a tomb (Matt. 27:57–61; 1 Cor. 15:4). On the third day, he rose from the grave (Acts 2:24; 3:15; Rom. 1:4; 1 Cor. 15:4) and appeared to many (1 Cor. 15:5–8). He later ascended to heaven (Luke 24:51; Acts 1:9), where he is seated at the Father’s right hand, making intercession for his people (Rom. 8:34; Heb. 7:25; 1 John 2:1).

One day, Jesus will physically and visibly return to judge the living and the dead (Matt. 24:36–25:46; Acts 17:31;1 Thess. 4:13–5:11; 2 Thess. 1:7–10; 2 Tim. 4:1; 2 Pet. 3:10–13; Rev. 19:11–21; 20:11–15). Jesus will then make all things new by bringing heaven down to earth to make a new creation (Rev. 21:1–22:5).

Jesus is the only way to be reconciled to the Father. He is the only way to be saved (John 14:6; Acts 4:12).

The Holy Spirit

I believe that the Holy Spirit is the third Person of the Trinity (Matt. 3:16–17; 28:19; 2 Cor. 13:14). As such, the Holy Spirit is Lord and God (Acts 5:3–4; 2 Cor. 3:16–18). The various actions of the Holy Spirit reveal that he is personal (John 14:26; 16:8–15; Acts 16:6–7; 1 Cor. 12:11; Eph. 4:30; 1 Thess. 5:19). Like the Father and the Son, the Spirit possesses divine attributes, such as eternality (Heb. 9:14), power (Mic. 3:8; Acts 1:8; Rom. 15:13, 19), omniscience (Isa. 40:13–14; 1 Cor. 2:10), and omnipresence (Ps. 139:7). The Spirit also has a role in creating and sustaining life (Gen. 1:2; Job 26:13; 33:4; Ps. 33:6) and regenerating souls (Ezek. 36:25–27; John 3:5–8; 6:63; Tit. 3:5), enabling people to confess that Jesus is Lord (1 Cor. 12:3).

In addition to regenerating souls, the Holy Spirit indwells the believer at the moment of faith, serving as a seal and a guarantee that we will receive an eternal inheritance (2 Cor. 1:22; 5:5; Eph. 1:13–14). He makes Christians and the Church a temple of God (1 Cor. 3:16; 6:19; Eph. 2:22). The Spirit bears witness that we are children of God (Rom. 8:16; Gal. 4:6). The Spirit distributes gifts to the church, empowering members to serve within the body of Christ (1 Cor. 12:11; for spiritual gifts, see Rom. 12:3–8; 1 Cor. 12; Eph. 4:7–11; 1 Pet. 4:10–11). The Holy Spirit also produces fruit in the lives of a believer (Gal. 5:22–23).

Additionally, the Holy Spirit inspired men to write Scripture (2 Tim. 3:16; 1 Pet. 1:10–12; 2 Pet. 1:21; see also Acts 4:25; Heb. 3:7).

Salvation

Subjectively, one is saved by repenting of sin and believing in Jesus (Acts 2:38; 3:19;16:30, 31; 17:30; 20:21; Rom. 10:9–10; Heb. 6:1). When one has true faith in Jesus, a transformed life of good works follows (Eph. 2:10 in relation to vv. 8–9; James 2:14–26). The Christian will then strive to complete his or her salvation by pursuing holiness (Phil. 2:12–13).

Objectively, salvation is God’s work from start to finish. It is by God’s grace, operating through the instrument of faith, that saves a person, and all of this is a gift of God (Eph. 2:8–9; Phil. 1:29). God takes people dead in their sin, draws them to Christ, makes them alive, and resurrects them on the last day (John 6:44).

God’s salvation of people can best be seen in Romans 8:29–30. God predestines his chosen people for salvation (also Eph. 1:3–6; James 1:18; 1 Pet. 1:1–2). Those whom God predestines, he calls. He makes sure that the gospel message is preached to them so they can repent and believe. Those who believe are also justified, which means that they are declared righteous. They are credited with Jesus’ perfect righteousness. Those who are justified are sanctified, which, in this passage, is described as being conformed to the image of Jesus. Finally, those people will be glorified, when the process of salvation is consummated and they receive resurrected bodies. Paul does not explicitly mention regeneration in this passage, but this, too, is a work of the Holy Spirit. First Peter 1:3–6 shows how salvation from the time of regeneration to glorification is God’s sure work.

The Church

The one true Church of God consists of all the redeemed who have been purchased with Christ’s blood (Acts 20:28; 1 Cor. 1:2; Rev. 5:9). The Church consists of all who belong to the new covenant, which was inaugurated by Jesus. Members of the new covenant are those who have been regenerated by the Holy Spirit, who know God personally (through faith in Jesus) and who have been forgiven of their sins (Jer. 31:31–34; Ezek. 36:25–27). Those who have been born again should also be baptized in obedience to Christ (Matt. 28:19; Acts 2:38). The Church is the one body of Christ, filled with the one Spirit, under the rule of the one Lord, possessing one faith and experiencing one baptism (Eph. 4:4–6). Jesus gave the Church apostles, prophets, evangelists, shepherds, and teachers to equip the saints for ministry (Eph. 4:11ff.). All members of the body of Christ have been given spiritual gifts to be used for worship and mutual edification (Rom. 12:3–8; 1 Cor. 12; Eph. 4:7–11; 1 Pet. 4:10–11).

The two offices within the church are pastors/elders/bishops/overseers and deacons (Phil. 1:1; 1 Tim. 3:1–13). The two marks of any church are a right handling of God’s Word (2 Tim. 2:15; 4:2) and a right administration of the two ordinances: baptism and the Lord’s Supper (Matt. 28:19; Rom. 6:2–4; 1 Cor. 10:14-22; 11:17-34; 12:13; Eph. 4:5; 1 Pet. 3:21).

The main tasks of the church are worship, mutual edification, and evangelism. The church should also practice church discipline in the manner prescribed by our Lord in Matthew 18:15–20 (See also 1 Cor. 5.) This is for the benefit of Christ’s reputation, the members of the church, and the one who is unrepentant.

Last Things

We live in a fallen, sinful world. Since Adam and Eve’s rebellion, in Genesis 3, the world and all humanity has been under a curse that includes pain, hard labor, and death. However, one day, God will restore his creation, transforming this earth into a new heavens and earth (Isa. 65:17; 66:22). This transformation will consist of a refining the earth by fire, through judgment, during which sin will be purged (2 Pet. 3:10–13). In the new creation, there will be no sin, no pain, and no death. There will only be a Paradise in which God and his people, redeemed by Jesus’ sacrifice on the cross, dwell (Rev. 21–22).

When Jesus rose from the grave following his death, he rose in a glorified, immortal body. He thus inaugurated the new creation. He is the firstfruits of the resurrection (1 Cor. 15:20). All who have repented of their sins and put their trust in Jesus have been born again of the Holy Spirit (John 3:1–8). This means they are a new creation. (2 Cor. 5:17), being changed from the inside out by the Holy Spirit, becoming increasingly like Jesus (Rom. 8:29). Though all humans will die, the spirits of those in Christ will join him in heaven (2 Cor. 5:1–10). Upon Jesus’ return, the dead in Christ will experience a bodily resurrection (1 Cor. 15:23, 51–53). They will then receive their own glorified, incorruptible bodies, ones that will be perfect and will no longer be hampered by the curse of sin. Jesus will wipe away every tear (Rev. 21:3–4). Only those who have faith in Jesus will experience this blessed eternal state. Those who have rejected God will be consigned to hell. They, too, will have a physical resurrection, but only to be judged and cast into the lake of fire, to be punished and tormented forever (Rev. 20:11–15).

The New Testament repeatedly testifies that one day, Jesus will indeed return. However, no one knows when this will occur (Matt. 24:36; Acts 1:7; 1 Thess. 5:1–2). The entire witness of the Bible seems to indicate that prior to Jesus’ return, things will get worse. It appears that there will be a great rebellion and a “man of lawlessness,” or the Antichrist, will appear (2 Thess. 2:1–12). Then Jesus will return suddenly and visibly, like a thief in the night (1 Thess. 5:2). Those who belong to Christ will be “caught up in the clouds . . . to meet the Lord in the air” (1 Thess. 4:13–18). It seems that they will return to earth, where there will be a great judgment. From my reading of the New Testament, this will happen quickly. It seems the destruction and judgment of unbelievers happens all at once. (It is possible that 2 Thess. 1:7–10; Rev. 19:11–21; and 20:7–15 are describing roughly the same timeframe.)

I believe that Revelation 20:1–6, the famous passage on the millennium, describes the time period between the two advents of Christ. At the cross, Satan was cast out of heaven (John 12:31) and bound (Matt. 12:29). This is also pictured in Revelation 12. From one perspective, Satan’s influence has been greatly diminished. Satan is bound and thrown into the pit so that he might not deceive the nations any longer (Rev. 20:2–3; cf. Matt. 28:18–20, when Jesus commissions his disciples to disciple all nations.)

Though we may disagree about the meaning of the millennium, we can all agree that one day, at a time when no one is expecting it, Jesus will return to reign, to judge, and to make all things new. We can all look forward to eternity with him. This indeed is our blessed hope.